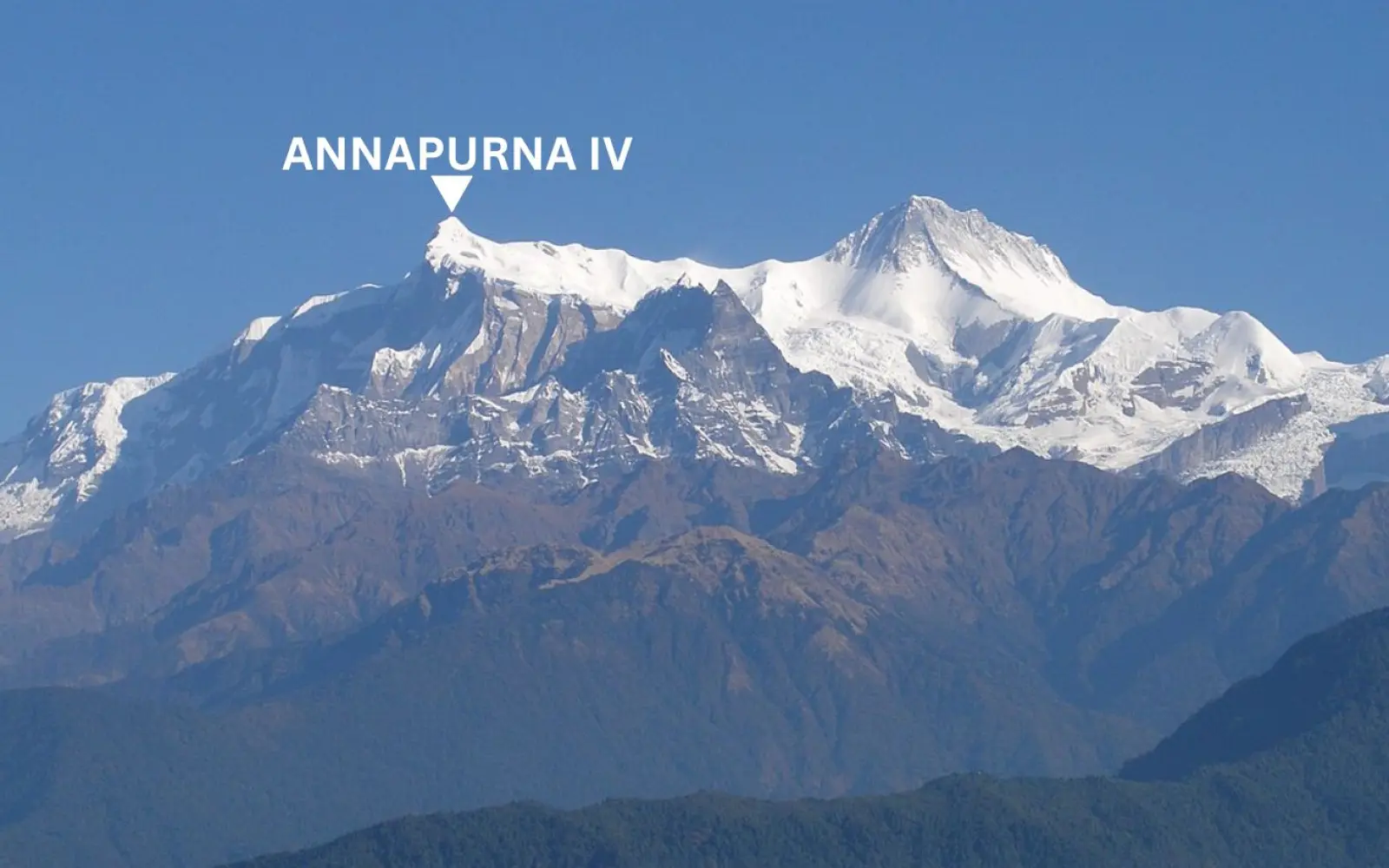

Annapurna IV (7525m) is a Nepal giant. See its 1955 first ascent, Manang trails, and top Annapurna Circuit viewpoints for Himalayan climbing photos.

The Annapurna massif in north-central Nepal represents one of the most complex and formidable geological structures in the global Himalayan chain. Within this frozen rampart, Annapurna IV stands at an elevation of 7,525 meters (24,688 feet), serving as a crucial, albeit often overlooked, anchor point for the eastern wing of the range. While its neighbor, Annapurna I, commands international attention as the world’s tenth-highest peak and a notorious "eight-thousander," Annapurna IV possesses a distinct character defined by its elegant pyramidal geometry, its strategic importance in the climbing routes of the massif, and its deep integration into the cultural and ecological fabric of the Marsyangdi Valley. Historically referred to as a "Silent Titan," the mountain offers a unique intersection of technical mountaineering challenges and some of the most accessible high-altitude vistas for trekkers traversing the world-renowned Annapurna Circuit.

Geographical and Tectonic Context

Annapurna IV is situated within the Gandaki Province of Nepal, occupying a central position in the Annapurna Himal sub-range. The Marsyangdi River geographically bounds it to the east and the Kali Gandaki Gorge to the west, a feature recognized as the deepest gorge in the world. The mountain is part of a high-altitude ridge system that connects it to Annapurna II (7,937 m) to the east and Annapurna III (7,555 m) to the west. This ridge forms a massive wall of ice and rock that includes several of the most significant peaks in the central Himalaya.

| Feature | Data Point |

| Elevation | 7,525 m (24,688 ft) |

| Latitude | 28° 32' 15" N |

| Longitude | 84° 4' 58" E |

| Prominence | 255 m (837 ft) |

| Isolation | 3.81 km (2.37 mi) from Annapurna II |

| Parent Peak | Annapurna II |

| Subrange | Annapurna Himal |

The mountain's prominence of 255 meters is relatively low compared to its absolute height, a characteristic resulting from its position on the high connecting ridge to Annapurna II. Despite this, it remains the 38th-highest peak in Nepal and the 55th-highest in the entire Himalayan range. Its isolation is marked by the Sabje La col, a deep gap that separates Annapurna IV from the eastern ridge of Annapurna III. This col is a significant geographical feature, providing a passage between the Marsyangdi drainage to the north and the Seti River valley to the south.

Tectonic Evolution and Lithology

The formation of Annapurna IV is the result of the ongoing collision between the Indian and Eurasian tectonic plates, a process that began approximately 50 million years ago. The structural integrity of the peak is defined by a series of metamorphic and sedimentary layers typical of the Tethyan Himalayan sequence. The summit and upper sections of the Annapurna massif are primarily composed of limestone, a fact that supports the theory that these peaks emerged from an ancient ocean floor.

Geological surveys in the Marsyangdi Valley indicate a stratigraphic record ranging from the Central Crystalline basement to the Jurassic Dogger formations. The Annapurna Range exhibits a large syncline with a northwest-southeast axis, overfolded from the south by a north-directed anticline. The increasing number of climate-associated disasters in the Himalayan region, which have significant impacts on human life and ecosystems, serve as indicators of contemporary climate change within this fragile tectonic setting.

The primary geological formations in the vicinity of Annapurna IV include several distinct layers. The Nilgiri Limestone is a Cambro-Ordovician succession between 3,000 and 4,000 meters thick, consisting of well-bedded limestones and medium-to-coarse-grained marbles. The North Face Quartzite is an Ordovician series of fine-grained, light-colored quartzites and siliceous limestones, often appearing as a distinct band above the bluish Nilgiri Limestone. The Tilicho Pass Formation is a Devonian sequence of turbiditic sandstones and argillites.

A notable event in the peak's geomorphological history occurred around 1190 AD, when a giant rockslide involving approximately 23 cubic kilometers of material collapsed a paleo-summit of the Annapurna massif. This event likely reduced the height of the ridge-crest by several hundred meters and had a massive impact on the sediment load of the rivers downstream for over a century. Such mega-rockslides represent a mode of high-altitude erosion that prevents the disproportionate growth of Himalayan peaks, effectively capping their potential elevation despite regional rock uplift.

Mountaineering History and First Ascent

The human history of Annapurna IV is one of methodical exploration and the transition from the "Golden Age" of Himalayan expeditions to modern technical climbing. While Annapurna I was famously summitted in 1950 by a French team led by Maurice Herzog, Annapurna IV remained unclimbed for another five years, serving as a secondary objective or training ground for teams eyeing the higher eight-thousanders.

The 1955 German Success

The first successful ascent of Annapurna IV was achieved on May 30, 1955, by a German expedition organized by the Deutsche Himalaja Stiftung (German Himalaya Foundation) in cooperation with the German Alpine Club. Led by Heinz Steinmetz, then 29 years old, the team was notable for its small size and disciplined approach, consisting of only four primary members: Harald Biller, Fritz Lobbichler, and Jürgen Wellenkamp.

The expedition approached through the Marsyangdi Valley, utilizing the route previously scouted by H.W. Tilman’s party in 1950. Tilman had reached approximately 24,000 feet (7,315 meters) but was forced to retreat due to exhaustion and deteriorating weather conditions. Japanese climbers had also attempted the mountain in 1952, reaching 19,000 feet.

The German team established their base camp in the Manang region and methodically pushed toward the Northwest Ridge. On the summit day, Steinmetz, Biller, and Wellenkamp reached the highest point after a grueling 12-hour push from their final high camp. The final summit ridge proved technically more difficult than anticipated, but excellent snow and ice conditions facilitated the ascent. Fritz Lobbichler had been forced to turn back at the "Dome" (a snow summit on the main ridge) due to poor physical condition, choosing to wait for his teammates to return.

| Expedition Detail | Information |

| Date of First Ascent | May 30, 1955 |

| Team Leader | Heinz Steinmetz |

| Summit Party | Heinz Steinmetz, Harald Biller, Jürgen Wellenkamp |

| Ascent Route | North Face and Northwest Ridge |

| Approach | Marsyangdi Valley / Manang |

The team’s success was followed by a remarkable series of climbs in the region; they summited several other peaks in the Damodar Himal and Lamjung Himal, totaling 11 mountains in a single season. This marathon of high-altitude success demonstrated the efficacy of their acclimatization strategy and established a precedent for smaller, highly mobile Himalayan expeditions.

Subsequent Notable Expeditions and the Himalayan Database

Following the 1955 ascent, Annapurna IV became a sought-after objective for climbers seeking a high-altitude experience without the extreme objective hazards of Annapurna I.

A Canadian team led by Gordon Smith achieved a successful winter ascent via the normal North Face route on December 22, 1982. Climbers Roger Marshall, Alan Burgess, and Adrian Burgess reached the summit in temperatures as low as -30°C and under "unreasonably strong" winds. This expedition was used as training for a Canadian attempt on Mount Everest and was marked by significant logistical challenges, as the snow line sat at 9,000 feet, making the approach with ill-clad porters extremely difficult.

In 1991, Richard Salisbury organized an expedition to Annapurna IV. While the climb itself was a significant undertaking, its more lasting legacy was the meeting between Salisbury and Elizabeth Hawley, a long-time journalist based in Kathmandu. Impressed by Hawley's deep knowledge and handwritten notes on expeditions, Salisbury proposed transferring her records to a computer database. This collaboration led to the creation of the Himalayan Database, which now serves as the world's most comprehensive record of Himalayan mountaineering.

The 1996 climbing season in the Annapurna Himal involved two separate American efforts marked by severe weather. Renowned climbers Alex Lowe and Conrad Anker used the south side of Annapurna IV to acclimatize for their attempt on the unclimbed southeast pillar of Annapurna III. They reached 7,200 meters but were trapped in a snow cave for a week by heavy snowfall. Meanwhile, a larger American party attempting Annapurna IV from the north side suffered a tragedy when Richard Davidson and Debbie Marshall were smothered to death in their sleep at Camp 1 (5,400 m) after their tent collapsed under a meter of fresh snow.

Technical Mountaineering and Route Description

Annapurna IV is technically graded as TD+/4 on the Alpine scale. While it is considered the least dangerous of the major Annapurna peaks—lacking the extreme avalanche frequency of the North Face of Annapurna I—it remains a serious mountaineering objective. Success on the mountain hinges on meticulous fixed-rope management, careful acclimatization, and identifying appropriate spring or autumn weather windows.

The Standard Northwest Ridge Route

The route first pioneered in 1955 remains the standard commercial and private route. The ascent is characterized by a mix of moraine traversing, technical rock slabs, and sustained snow and ice slopes. Modern expeditions typically employ three to four high camps to facilitate the summit push.

Base Camp to Camp 1 (4,800 m – 5,500 m)

Base Camp is typically situated at approximately 4,800 meters, reachable from the village of Humde or Manang after several days of trekking and acclimatization. The first phase is described as the "crucial initial technical phase" and involves traversing a moraine glacier to reach the base, followed by a challenging ascent of steep, rocky slopes. Teams establish fixed lines on sharp rock slabs with inclines ranging between 60° and 80°.

Camp 1 to Camp 2 (5,500 m – 6,200 m)

The route from Camp 1 leads through loose rocky terrain to a "crampon point," where the surface transitions to permanent snow and ice. This section includes an 80° steep climb across icy and snowy terrain. While the route carefully skirts the left side of the mountain to avoid avalanche-prone areas, climbers must navigate manageable crevasses, often requiring calculated leaps while secured to fixed lines.

Camp 2 to Camp 3 (6,200 m – 6,800 m)

This phase involves a ridge-line ascent consisting of mixed snow and rock. Camp 3 is often positioned at approximately 6,800 meters near the "Dome," a snow summit on the main ridge. This location provides spectacular views of the North Face of Annapurna II and is situated at the junction of the North Ridge and Summit Ridge.

Camp 3 to Summit (6,800 m – 7,525 m)

The final push to the summit is a daunting 1,000-meter vertical climb that typically takes 12–14 hours round trip. Some teams establish a Camp 4 at 7,000 meters on a flat but windy surface to break up the effort. The route involves moderate to steep snow slopes and the use of fixed ropes on overhanging or perilous sections of the mountain walls. The true summit is a narrow point that requires careful rope management due to exposure.

Objective Hazards and Regional Rescue Dynamics

The primary dangers on Annapurna IV are weather-related rather than structural. Unlike Annapurna I, which has been labeled the "deadliest mountain on Earth" with a fatality rate of approximately 30%, Annapurna IV is relatively stable and lacks the extreme serac collapse risk of its higher neighbor. However, the mountain is notorious for extreme wind speeds, particularly on the Northwest Ridge and the summit plateau.

High-altitude pulmonary and cerebral edema (HAPE and HACE) are constant risks, as the climb involves a rapid ascent from the Marsyangdi Valley. Recent rescue operations in the massif illustrate the technical difficulty of operations at these altitudes. In April 2023, Indian climber Anurag Maloo was rescued from a 60-meter deep crevasse between Camp 3 and Camp 2 on Annapurna I. The rescue required a complex pulley system and the descent of world-class climbers like Adam Bielecki into the crevasse. Such events underscore the necessity for climbers on Annapurna IV to be self-sufficient and well-versed in crevasse rescue techniques.

The Marsyangdi Valley and Trekking Infrastructure

Annapurna IV is a dominant silhouette for trekkers on the Annapurna Circuit, a route that encircles the entire massif and is widely considered one of the premier trekking experiences globally. The journey through the Marsyangdi Valley provides a front-row seat to the mountain's changing faces as trekkers ascend from subtropical lowlands to high-altitude deserts.

The Approach: From Besisahar to the Trans-Himalaya

The trek typically commences in Besisahar or Syange, where the environment is characterized by lush subtropical forests, rice terraces, and waterfalls. As trekkers move toward Dharapani and Chame, the vegetation changes to alpine forests of pine and fir.

Chame (2,710 m) serves as the administrative headquarters of the Manang district and offers one of the first framed views of Annapurna IV. From here, the trail winds through dramatic gorges, including highlights like the Paungda Danda, a massive curved rock face rising more than 1,500 meters from the river, which is considered sacred by local communities.

Upper Pisang (3,300 m) represents a significant transition point. Situated on a limestone ridge, it offers panoramic views of Annapurna II, III, and IV. The stone houses are clustered around a small monastery that overlooks the valley, providing a dramatic backdrop for the towering peaks. Trekkers often choose the "Upper Route" through Ngawal (3,660 m), which remains hundreds of meters above the valley floor and provides an unbroken vista of the Annapurna horseshoe.

Manang: The Cultural and Acclimatization Hub

The village of Manang (3,540 m) is the primary staging ground for both trekkers and expeditions. Located in the rain shadow of the Annapurna Range, the environment is arid and desert-like, distinctly different from the lush valleys just a few days' walk to the south. Manang provides essential facilities, including guesthouses, bakeries, and the Himalayan Rescue Association (HRA) medical clinic, which offers altitude counseling to prevent Acute Mountain Sickness (AMS).

Trekkers often spend several days in Manang to acclimatize before attempting the Thorong La Pass. During this time, several side trips provide intimate views of Annapurna IV:

- Gangapurna Lake: This turquoise glacial lake is formed by meltwater from the Gangapurna Glacier. A short hike to the viewpoint above the lake offers a direct look at the ice walls of Annapurna IV and Gangapurna.

- Ice Lake (Kicho Tal): Situated at 4,620 meters, this lake acts as a natural mirror, reflecting Annapurna II, III, and IV on clear days.

- Braga Monastery: Located in the village of Braga just before Manang, this 500-year-old gompa is one of the oldest in the region and houses significant Tibetan Buddhist artifacts.

Cultural Heritage and the Manangba People

The region surrounding Annapurna IV is deeply influenced by Tibetan Buddhism and the unique trade history of the Manangba people. The mountain itself is part of a landscape where natural features are inextricably linked to spiritual entities.

Religious Significance of "Annapurna"

The name "Annapurna" is derived from the Sanskrit words Anna ("food") and Purna ("full" or "complete"). In Hinduism, Annapurna is the goddess of nourishment and abundance, representing the essential elements needed for life. She is often viewed as an incarnation of Parvati, the consort of Lord Shiva. The rivers that flow from the massif, such as the Marsyangdi, are seen as the goddess's blessings, providing the lifeblood for agriculture in the plains of Nepal.

The Manangba Trade Legacy

Historically, the Manangba (or Manangé) were central to the trans-Himalayan salt trade, which served as a primary corridor for exchanging Tibetan salt and wool for Nepalese rice until the early 1960s. Traders used sheep, goats, and yaks to traverse high mountain passes, and the barter of grains for salt formed the basis of the local economy.

A unique historical privilege granted by the Shah and Rana rulers of Nepal allowed the Manangba to travel freely throughout the country and exempted them from paying customs duties. When the salt trade declined following the 1950 Chinese annexation of Tibet and the 1962 Sino-Indian War, the Manangba utilized these special privileges to pivot toward international trade. They began traveling to Southeast Asian cities like Bangkok, Kuala Lumpur, and Hong Kong to trade in herbs, gemstones, and semi-precious stones. This international exposure brought relative wealth to the valley, which is evident in the sophisticated stone architecture and well-maintained monasteries of Manang today.

Festivals: Yartung, Losar, and Mani Rimdu

Cultural life in the shadow of Annapurna IV is punctuated by vibrant festivals that blend Buddhist and pre-Buddhist traditions:

- Yartung (Horse Festival): Celebrated primarily in Manang and Muktinath during the full moon of August. This multi-day festival marks the end of summer and the harvest season. Horses are brought back from high-altitude pastures where they graze freely for four months, and villagers compete in horse races that test both speed and skill. It is a ritual that honors the ancient bond between Himalayan men and their horses, dating back to eras of frequent inter-village conflict.

- Losar (Tibetan New Year): Celebrated in February or March, Losar is the most important festival in the upper Annapurna region. Families clean their homes, raise new prayer flags, and gather at monasteries for chanting and masked dances.

- Mani Rimdu: Held in the autumn at Braga Monastery, this festival involves several days of masked "Cham" dances and rituals performed by monks to bring peace and prosperity to the land.

Ecology and Biodiversity within the Annapurna Conservation Area

Annapurna IV is protected within the Annapurna Conservation Area (ACA), which was established in 1985 as Nepal's first and largest protected area, covering 7,629 square kilometers. The region is a biodiversity hotspot, containing 1,226 species of flowering plants and over 100 mammal species.

Altitudinal Vegetation Zones

The massive altitudinal gradient from the Marsyangdi River to the summit of Annapurna IV creates distinct ecological zones:

- Subtropical and Temperate Zones (1,000 m – 3,000 m): Characterized by forests of Schima-Castanopsis, Oaks, and Rhododendrons. The national flower, Rhododendron arboreum, blankets the lower hillsides in crimson and pink during the spring.

- Subalpine Zone (3,000 m – 4,000 m): Forests of Birch (Betula utilis), Blue Pine, and Juniper.

- Alpine Zone (above 4,000 m): Stunted shrubs, hardy grasses, mosses, and lichens adapted to extreme cold and low oxygen.

Protected Wildlife and Birdlife

The ACAP is home to several globally threatened and endangered species. The Snow Leopard (Uncia uncia) is a flagship species of the high Himalaya, and initiatives such as community-based conservation and anti-poaching patrols are active in the region to protect this elusive predator. Other notable mammals include the Himalayan Musk Deer, Red Panda, and Blue Sheep (Bharal), the latter of which is a key prey species for the snow leopard.

The region is also a birdwatcher's paradise, with 486 species recorded. It is the only protected area in Nepal that hosts all six of the country's Himalayan pheasant species, including the Impeyan Pheasant (Danphe), which is the national bird of Nepal.

Logistics, Regulations, and Permits

Mountaineering in Nepal is strictly regulated by the Ministry of Culture, Tourism, and Civil Aviation. Effective September 1, 2025, the government introduced a significant hike in permit fees to improve safety, environmental protection, and local infrastructure.

Updated Permit Fee Structure (2025/2026)

For peaks between 7,001 m and 7,500 m, which include Annapurna IV, the royalty fees for foreign climbers have been adjusted:

| Season | Royalty Fee (Foreign Nationals) | Royalty Fee (Nepali Citizens) |

| Spring (March–May) | $800 | Rs 40,000 |

| Autumn (Sept–Nov) | $400 | Rs 20,000 |

| Winter/Summer | $200 | Rs 10,000 |

In addition to the mountaineering royalty, all participants must secure an Annapurna Conservation Area Permit (ACAP) and a Trekkers’ Information Management System (TIMS) card. Expeditions are also required to hire a government-appointed Liaison Officer and provide mandatory insurance for all Sherpas and support staff.

Accessibility and Approach

Reaching the vicinity of Annapurna IV has been simplified by the extension of road networks. Trekkers and expeditions can now take 4WD jeeps from Besisahar to Chame or even as far as Manang in some seasons. However, the road remains rugged and prone to landslides during the monsoon. Domestic flights to the Humde airstrip in Manang provide an alternative, although they are weather-dependent and less frequent than road travel.

Viewpoints and Photography

Annapurna IV is one of the most photographed peaks in central Nepal due to its symmetry and its position relative to the low-lying Marsyangdi Valley. The best views are found along the high route of the Annapurna Circuit.

- Upper Pisang: Offers a linear perspective of the Annapurna wall. At sunrise, the light first strikes the summit of Annapurna IV, creating a "halo" effect.

- Ngawal Viewpoint: Provides a panoramic view of the Annapurna horseshoe. The air in Ngawal is particularly thin and crisp, making it ideal for sharp, high-contrast landscape photography.

- Ice Lake (Kicho Tal): A day hike from Manang to 4,620 meters offers a 360-degree panorama. On clear mornings before the afternoon winds stir the water, the lake provides a perfect reflection of Annapurna II, III, and IV.

- Gangapurna Lake: Accessible from the center of Manang, this lake offers a close-up view of the glaciers descending from Annapurna IV and Gangapurna.

For photography, the Golden Hour, approximately 30 to 60 minutes after sunrise and before sunset, is the best time to capture the warm orange hues on the mountain's faces. Using a circular polarizer is highly recommended to deepen the blue of the high-altitude sky and manage the intense glare from the snow.

Annapurna IV remains a cornerstone of the Himalayan experience, balancing technical mountaineering challenges with an unparalleled accessibility for those traversing the

Annapurna Circuit. As the "Silent Titan," it provides a stark contrast to the commercialized and often overcrowded eight-thousanders, offering a sense of isolation and aesthetic beauty that recalls the golden era of exploration. Whether viewed from the prayer-flag-lined ridges of Ngawal or climbed through the steep rock slabs of its Northwest Ridge, Annapurna IV embodies the "Goddess of Abundance," sustaining the ecosystems, cultures, and dreams of all who venture into its shadow.